How to Go Beyond Metaphysics?

Clarifying the meaning of the Transcendent

In a previous post, I argued that we can participate with transcendent, eternal, and infinite Truths through logic. This is possible because logic, by preceding metaphysics, renders the logical forms we comprehend timeless and transcendent. That is, they're not limited only to this universe. You can find this post below:

I didn't clarify my approach as clearly as I could have, and many comments expressed some skepticism about the idea. Specifically, there were doubts about the possibility of going beyond metaphysics. That is to say, to step outside of our particular embodied experience in this tangible metaphysical world. [Thanks, by the way, for all the insightful comments.]

This led me to further reflect on the meaning of the transcendent and what it means for logic to be independent of metaphysics.

Let me be clear then. I’m not claiming that, through some mental technique or some other magic trick, we would be able to detach ourselves from our embodied existence and access some esoteric and occult dimension from which we could reach the transcendent. This would be a gnostic idea that actually imposes a dualistic metaphysics of matter and spirit.

On the contrary, I think it is an obvious fact that our starting point lies in our current state of mind, in human bodies, in this particular time, with all the habits and instincts we’ve embodied through our lives and evolution. Peirce is clear about this:

But in truth, there is but one state of mind from which you can ”set out”, namely, the very state of mind which you actually find yourself at the time you do ”set out,”—a state in which you are laden with an immense mass of cognition already formed, of which you cannot divest yourself if you would; and who knows whether, if you could, you would not have made all knowledge impossible to yourself? (EP2: 336, 1905)

How then could we ever transcend the boundaries of our contingent existence? Aren’t we then prisoners of it?

It’s the Same Frenchman Again

These questions are the starting point of modern philosophy. Given the nature of modern philosophy, it has become impossible to begin inquiry without asking how we can know the reality beyond our own cognition.

But this hasn’t always been so. Again the same old Frenchman, René Descartes, played a pivotal role in shifting our philosophical focus to individual minds. After Descartes it has become the norm to privilege the contents of our individual minds and regard internal representations as more real than external ones. Often we call these internal representations intuitions and they are regarded as the most real thing there is.

Modern philosophy has then tried to identify some ultimate intuition to serve as the cornerstone for constructing a fully objective and justified philosophical framework. The cornerstone must be a self-justified and indubitable proposition. From this proposition, a series of deductions are then made, forming the edifice of philosophy.

This was the method of Descartes, who put down the cornerstone “I think, therefore I am”. In a sense, it is a self-justified proposition, because an objection of it leads to a performative contradiction. If I say that “I am not, although I think” or that “I can’t be sure that I exist, although there is an I who is not sure about its own existence” I’m asserting paradoxical statements.

“Perfect”, thought René . But then a horde of skeptics arrived and asked: “Okey, so there is an I, but what about its relationship to the not-I, that is, to the external reality. How can we be sure about its existence?” For Descartes this was secured by the benevolence of the Divine Creator, but that didn’t satisfy the skeptics.

This led to a back-and-forth, giving rise to rationalists and empiricists, who united against the skeptics. And without many noticing, the question of the external world emerged in many ways as the central problem of modern philosophy. I have written about this theme in the following post:

But how did we end up in this specific problem? The reason for this is that we started with metaphysics.

By asserting that there is an I and the not-I, an individual mind experiencing and the external world causing these experiences, we have asserted a strong metaphysical claim before the inquiry even begins.

This is an a priori claim about the nature of reality. Before we let experience determine anything we have already decided what kind of experiences are more secure than others and what is the nature of experience.

If we begin with the idea that our mind is disconnected or separate from the external reality, we limit our inquiry from the get go. We begin by fitting everything we experience into this mentalistic, ultimately solipsistic, frame.

In my opinion this simply isn’t the right way to do philosophy. We can’t begin with metaphysics. Shouldn’t we begin from the experience in itself without trying to immediately justify or judge it? Shouldn’t we begin with phenomenology, or what Peirce called pharenoscopy?

What is the Transcendental Method?

Immanuel Kant, was on the right track when he asked the question: What is necessary to our experience? What are the fundamental categories — the structure or framework — of experience? In this search he famously derived the transcendental categories forming the fundamental a priori structure of human mind.

But isn’t this a priori as well, and therefore, limiting inquiry? To tackle this question, we must have a clear understanding of what the transcendental method really is.

The transcendental method is not something detached from our experience. It is not armchair philosophy that invents some set of logical categories or propositions and then performs various lines of deductions from them in order to construct a rigid philosophical system. Rather, according to Gabriele Gava1, the transcendental method begins from our experience as such.

The transcendental method tries to abstract, or in Peirce’s language, prescind, the elements that are necessary to the phenomenological immediate experience. Prescission is attention to one element and neglect of the other.

For example we can prescind instantiations (2ndness) from patterns (3rdness). For instance, a lane marking is a regular pattern signifying driving lanes, while each individual line of paint is an instantiation of that pattern. While you can focus on a single line without considering the entire pattern, the attention to the pattern itself inherently involves recognizing and considering its instantiations.

Furthermore, we can prescind qualities (1stness) from instantiations (2ndness). For instance, you can contemplate the qualities of the individual painted line—such as its color—without specifically considering the particular instantiation of that line. However, you cannot cognize the individual instantiation of the line without attending to its qualities.

When thinking of an instantiation you can thus disregard the pattern and fill your mind with the forcefulness of the instantiation. And when thinking of the qualities of the instantiation you can disregard the forcefulness of it and be immersed in the qualities themselves.

Through this method, we can abstract the most general elements of our experience, elements without which the experience would be impossible. According to Peirce, these elements are the three categories of 1stness (quality), 2ndness (forcefulness) and 3rdness (mediation), which form the most fundamental and general structure that must always be present in every possible experience. You can read more about the categories in the post below:

The point is that we start with experience as it is. We don't begin by justifying its objectivity or pondering its relation to the external world. This isn't a concern in phenomenology. We're interested in uncovering the most general aspects of our experience, whether it's a feeling, tactile sensation, action, thought, daydream, hallucination, or scientific observation.

The question isn't about the validity of our experience, but its fundamental structure. It's not about the matter, but the form. To be clear, yes, what we are inquiring is our experience, i.e. semiosis as experienced by the human mind, but our task is different compared to modern philosophy.

It's a different mindset. We're not arguing our way into indubitable philosophical certainty. Instead, we're inquiring, with an open heart, into the structure that's already present in every moment. It's not a project of building, but a process of discovery.

Esthetical Ideal as the Motivating Driver

The fundamental difference between the categories of Kant and Peirce is that Peirce’s categories are dynamic and evolving: 1stness wants to be original, overflowing with novelty, 2ndness just wants to express itself with force, and 3rdness wants a body that could manifest its coherence and order. This interplay where one is creating, second is expressing, and third is bringing order, is the process of reality. It is like the co-operation of a play writer, an actor and a director.

The three categories are the three flavors of reality that can be combined in infinite different ways giving us infinite novel perceptions. They can’t ever be exhausted by their instantiations.

Now the categories are great by themselves, but the dynamic process still needs some kind of a motivation or a driver. What guides our inquiry? What is the organizing principle in our experience? What are we searching for?

In order for us to experience and inquire we need to have some guiding principle which organizes them. Our inquiry can’t be just a sporadic set of movements in every direction based on random impulses. We need to have an aim, a telos, which brings cohesion and purpose to our action— an esthetical ideal.

This is where the next science, esthetics, comes in. It’s job is to inquire the form of the ultimate aim. Normative sciences are all about this esthetical ideal. What makes one an ultimate esthetical ideal (esthetics) and how to approach it through action (ethics) and thought (logic). In other words, if there is Beauty, Goodness and Truth, normative sciences inquire how to draw closer to them.

The Metaphysical Move

The problem of the external world is, however, not resolved. Aren’t we still trapped inside our minds? Aren’t we only prescinding the structure of our own mind and not the structure of reality? It is at this point we bring metaphysics into the picture.

The answer to this problem is an earnest hope. In order to inquire we need hope that our questions can be answered. This is the metaphysical doctrine that posits that the categories that are necessary for our experience are the same categories that are operative in nature.

This statement dissolves the gulf between our mind and the external reality. There is no inherent difference between the structure of our experience and the structure of reality. We both live on a common continuum (the doctrine of synechism). Our experience is determined both by the structure of our mind and by the structure of reality, and these are in the last analysis the same thing.

This is the metaphysical move. Yes, all we experience are representations. But the nature of reality is also representational. The universe is a representation. The universe is a sign, and so are we. The form is the same, so we can potentially capture, through the use of symbols, the form of the reality just as it is.

But this is an endless process, not a static procedure. The reality, because it has the nature of a representation, is constantly flowing, moving and fluctuating. It can’t be contained or put in a box. The reality is both forever evading our representations and being ever more truly represented in our representations. Reality is thus becoming. It is an unending symphony.

Reaching the Transcendent

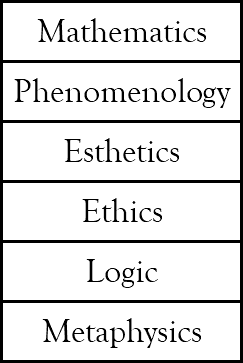

In the post “Escaping the Abyss of Nihilism” we explored the place of logic among the other sciences and saw how it must precede metaphysics. In this post we have explored the other side of logic, that is, the sciences that precede it. These are the sciences of mathematics, phenomenology (or phaneroscopy), esthetics and ethics.

But where does this lead us? How can we reach the transcendent?

The ability to reach the transcendent is predicated on the claim that the logical structure of our mind is the same as the structure of reality. Not only are the categories the same, but also esthetical Beauty, ethical Goodness and logical Truth are shared between us and reality.

In the last analysis, human esthetics are not different from the esthetics of the universe. This is why nature is so beautiful, why the earth and space captivate us, and why life itself is filled with beauty. It is not because our taste stems from a detached and arbitrary human experience, but because our taste, in the last instance, is the cosmological taste. We are a universe inside the universe. A fractal inside fractals constituted by fractals. The man is a microcosm.

However, it is true that with this ability to build our own universes inside the universe, like institutions, religions, and culture, we are able to bypass the tendencies and symbols of nature, creating our own independent representations of the universe that guide and govern our lives.

So yes, we can build castles in the air and produce hallucinations and false ideas. We are capable of rejecting reality and choosing to live in our fantasy worlds. We are fully capable of resisting the Truth in a way that other animals are not.

But at some point our representations have to match with reality, as we live on the same shared continuum. In the end, the shear brutality of reality forces us towards the Truth.

The point is that when our representations are brought into harmony with reality, there is no unbridgeable gulf between them. There is nothing destined to detach our representations from reality, as they share the same form. Both are representations, having the same logical structure. This is what it means for logic to precede metaphysics.

Our representations are controlled hallucinations that, through communal scientific inquiry, slowly but surely approximate the fundamental nature of reality. This allows us to comprehend the logical structure beyond the manifested universe—namely, the transcendent Beauty, Goodness, and Truth.

The transcendent is reached from within.

Thank you for reading!

Sincerely,

Markus

This post relies heavily on the wonderful and insightful work of Gabriele Gava. Here are the main sources used in this post. I highly recommend all of these articles.

The Purposefulness in our Thought: a Kantian Aid to Understanding Some Essential Features of Peirce (2008)

Does Peirce Reject Transcendental Philosophy? (2011)

Peirce’s ‘Prescision’ as a Transcendental Method (2011)